#teaching

I use three main tags on this blog:

-

hypertext: linking, the Web, the future of it all.

-

garage: art and creation, tinkering, zines and books, kind of a junk drawer - sorry!

-

elementary: schooling for young kids.

#teaching

I use three main tags on this blog:

hypertext: linking, the Web, the future of it all.

garage: art and creation, tinkering, zines and books, kind of a junk drawer - sorry!

elementary: schooling for young kids.

h0p3’s words: “I want to run around and hug everyone I’ve ever met.”

Okay, so, h0p3 has stumbled on to something pretty special—he asks, “Why aren’t other people losing their shit over this too?” This blog by Ian Wright (and, can I say, I love that this rare trove lives at the unassuming ianwrightsite.wordpress.com) is valuable for its writing and diagrams covering an intersection of certain math functions and philosophy, with aim toward understanding Marxism in modern times, all of which I’m just starting to pry open.

h0p3 specifically points to the two- (three-?) part essay “Hegelian contradiction and the prime numbers”, which I can’t vouch for yet. But the intro post and my light skimmings look promising. With a blog like this, I tire of the severe headiness—there never seems to be enough practicality or enough realization of the constructs—and the diagrams have me worried—but the writing is crisp and clear so far.

I hate getting my hopes up like this, because now I have some sense of a hidden or elusive truth buried in the center of this blog—and I’ve felt that almost constantly when approaching socialist blogs. But I need to remember that it’s just a blog: it’s not possible for it to have the answers and what’s usually lacking is enough imagination on my part. So this is sweet.

This post accepts webmentions. Do you have the URL to your post?

You may also leave an anonymous comment. All comments are moderated.

Brilliant talk by @tripofmice: a good introduction to maps, but also, hey, how to generate a world.

This talk is ostensibly about cartography, but has a lot of curious details that I think are applicable to any kind of technology—but definitely very applicable to the Public Self-Modelers out there.

The speaker, Mouse Reeve, makes a comment (at 11’29") about maps as ‘models’:

I like to think of a map as a model. And the process of making a map is the process of modeling. And models are inherently incomplete. And this is really, really good because it means you can never finish. And, um, if we could make a model that perfectly represented what we were modeling, it would raise a lot of really disturbing philosophical and ethical questions also—in terms of pocket universes.

Emphasis mine. (Obviously—it’s so rare that one hears vocal italics.)

This has really crystallized for me the new excitement over those

of you out there who are starting to hypertext yourselves in TiddlyWikis. I

have not been doing this—this blog is an old-fashioned style links-and-essays

blog that just kind of acts as a portal between all of you. And part of my hang

up has been what m.r. says: that a model is always incomplete. ( C’est n’est

pas une h0p3.)

C’est n’est

pas une h0p3.)

But then comes the line: this is really, really good. And I find that I truly agree with this! And even the ending line suggests that a perfect equivalence in a model may not even be desirable! (Like: thank god that Magritte’s pipe is not just a pipe.)

m.r.'s website is here, which fits right in with my monthly href hunt. The generated maps are at unfamiliar.city.

This post accepts webmentions. Do you have the URL to your post?

You may also leave an anonymous comment. All comments are moderated.

This post accepts webmentions. Do you have the URL to your post?

You may also leave an anonymous comment. All comments are moderated.

h0p3’s wife does a mic check.

(This is sooo cool—to get a response from h0p3’s wife on her own personal wiki. I just can’t believe we’re having these conversations. This was not what I intended to do on this blog. I actually didn’t have any intentions really—I just wanted to mess with hypertext again—which I guess opened me up to reading random TiddlyWikis and having these delightful, possibly pointless, just-for-funsies conversations. It’s better than anything that I could have intended to do.)

k0sh3k! First off, I love ILL, too. I am a massive cheapskate and I try to avoid clutter—but mostly I just like the weird editions that show up. And I like to see where the books come from. (I give a shoutout to this in my Stories/Novels page.)

My favorite was when Denton Welch’s Maiden Voyage came in. It was an ancient hardback from the 1950s. (It was the first book I read by him—I love him now.) As I read, I began to realize that this edition had been published right after he died (at age 33) and it really transported me to that age. I had a hard time giving that one back.

I actually should read The Educated Mind again before I recommend it. I went back and read my review—and some of my perspectives have changed since then. A lot has happened in four years. I still think I would love that the book bows before the visage of Socrates… (I am not a fast reader.)

My favorite poet is e.e. cummings, and if you haven’t read his work, you should.

I loved him in high school—I guess I have forgotten so much about him. I think I liked him at the time for gimmicky reasons. I know I saw past the mere shape of his poems. I thought he was funny. But to hear about ‘anti-industrialist poems’—you shouldn’t have lost that paper.

You’ll have to excuse the place - I only started keeping this to make h0p3 happy and to be a good example to the kiddos, although I’ve started keeping things here just for fun, too.

I am not nearly as good at keeping a wiki as h0p3 is; I haven’t gotten much better on any of this web stuff since the early days of chat rooms.

I think it’s charming. Your worries about organization or curating—sure, it’s fun to spend time on that stuff—but you’ve put a lot of work into what you’ve got already and it’s already very amusing and interesting to idly search and click around. I like that it’s informal. I like that it’s off-the-cuff.

I feel I should apologize for reading. It feels voyeuristic. Or like a robot eating up feelings. (CAN DESPISING AYN RAND REALLY FEEL THIS GOOD.) And maybe I am just scoping up anecdotes and recommendations in slapdash—this is just my own librarian way. It is shameful, it is noble—it is just a way to pass the time.

I think education, across the board, including college level, has hit a rough patch. It’s no longer about helping individuals become good, ethical human beings; it’s about shaping individuals into efficient little workers and consumers. I’m glad we have the chance to raise our kiddos to be good persons, and to recognize the systemic evils that use others as mere means for wealth accumulation.

Most of the teachers I’ve met and worked with are aware of this and frustrated by it, too. It’s strange to me that this awareness has been around since at least the 1970s—yet it’s only gotten worse, I’d hazard.

There was a conversation between Seymour Papert and Paulo Freire back then that really—well, it might have gone too far in places, but I think it’s mostly right on:

Now there comes a time when the infant is seeing a wider world than can be touched and felt. So the questions in the child’s mind aren’t only about this and this and this that I can see, but about something I heard, saw a picture of, or imagined. And I think here the child enters into a precarious and dangerous situation because not necessarily, but, I think, in point of fact in our societies, there is now a shift from experiential learning—learning by exploring—to another kind of learning, which is learning by being told: you have to find adults who will tell you things. And this stage reaches its climax in school.

And I think it’s an exaggeration, but that there’s a lot of truth in saying that when you go to school, the trauma is that you must stop learning and you must now accept being taught. That is stage two: it’s school, it’s learning by being taught, it’s receiving deposits of knowledge. I think many children are destroyed by that, strangled. Some, of course, survive it, and all of us survived it, and that’s one reason it’s often dangerous discussing these questions among intellectual people. In spite of the school what happened to us was that in the course of this stage two we learned certain skills. We learned to read, for example; we learned to use libraries; we learned how to explore directly a much wider world.

Now I think that there’s an important sense in which stage three is going back to stage one for those who’ve survived stage two—creative people in any field, whether in a laboratory or in philosophy—whether artists, businessmen, journalists—all the people in the world who are able, despite all the restrictions, to find a way of living creatively. We are very much like the baby again. We explore; it’s driven from inside; it’s experiential; it’s not so verbal; it’s not about being told.

To me, I agree that the scaffolding is important—but I think we tend to make the whole thing about scaffolding and public school tends to be all scaffolding all the time. But I think of scaffolding as being rough-shod. You hammer together a few planks and then get back to the building itself. The scaffolding goes away with time. You forget it was ever there.

(In case this is too vague—I tend to make ‘scaffolding’ synonymous with ‘adult assistance’, Vygotsky’s meaning, rather than the other meanings that float about from time to time.)

Of course, I think the above goes wrong a bit because I view reading as experiential and driven from inside—and I think even “telling” can be this way. Teaching can be very immersive and very improvisational. It’s difficult to know if it can ever be prescribed. (I don’t often watch television, but I think this is one thing that has kept me watching The Good Place—the main character is provided with a personal philosopher, a man who finds himself given an Herculean chore to try to prescribe his wisdom to her, even though it all is completely applicable. It simply cannot be told I think.)

Thank you for all the books and links—I will always be on the lookout for more and I am glad to know you and your family. While I’m interesting in the pioneering work you all are doing with wikis and such, I think it’s eclipsed by the effort you make among your two children. These words might be, at their height, a ‘model’ of us.

But they are only artifacts compared to the humans behind them. This j3d1h and kokonut seem like great additions to our reality. (Just from things they pop off with in h0p3’s writings.)

This post accepts webmentions. Do you have the URL to your post?

You may also leave an anonymous comment. All comments are moderated.

I think the iPad Mini could have reshaped pre-reading education, but it didn’t get a chance to.

The iPad mini, which was last upgraded in 2015, and the 9.7-inch iPad, last refreshed in March, won’t be upgraded, a person familiar with the company’s plans said.

Chromebooks are the new fashion in elementary school. They are cheap; they are everywhere. And they are unusable by kids in kindergarten through, in some case, third grade.

Sure, by now children can do some rudimentary typing and mouse flicking. But if you think trackpads are awful for adults, you should observe children using them. Tears, people.

I like this—from an abstract I saw recently:

The choice of the proper device can lead to benefits in terms of user engagement, which often is the prerequisite for learning. There are also additional dimensions to consider, as the usability and the physical fatigue. Their undervaluation, in an educational context, can hamper the successful outcome of the experience.

The iPad Mini was the first device in a very long time that I was truly excited about. In my mind, the most underserved group in our educational system is the pre-reading group from K-2, which cannot be served by the current Internet and which are largely given mobile edutainment apps.

Despite that—the touchscreen is watershed technology for this group. And younger:

Children as young as 24 months can complete items requiring cognitive engagement on a touch screen device, with no verbal instruction and minimal child–administrator interaction. This paves the way for using touch screen technology for language and administrator independent developmental assessment in toddlers.

In my experience, using Chromebooks and iPads among these groups, the tablets far outshine—a child is able to immediately speak its language. Sure, time spent learning a Chromebook can be useful. But making the device an end unto itself is part of our problem—language is technology and technology is language.

The language that toddlers are picking up on their parents’ phones can be built upon in school. This is a great benefit—since it has been very difficult to map gamepads—another similar ‘language’ form—to education.

And yet, we have so many problems:

Apple has recently put a $299 price for schools on their standard iPad, but Chromebooks are still eating them alive. I’m afraid that this signal away from the iPad Mini could set us back for the foreseeable future.

If only we could see an era where a $199 iPad Mini flourished among second grade and lower. This age group needs a breakthrough.

This post accepts webmentions. Do you have the URL to your post?

You may also leave an anonymous comment. All comments are moderated.

The thing—the key—the realization that’s needed before you can write shaders. Really, I think this will help.

This post accepts webmentions. Do you have the URL to your post?

You may also leave an anonymous comment. All comments are moderated.

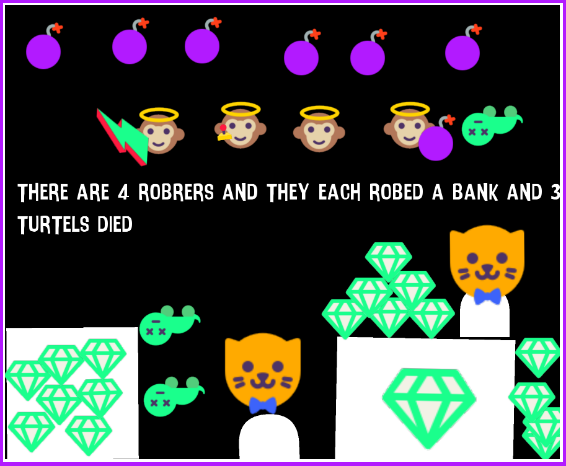

I often have the students concoct their own story problems. I highlight the most insane.

I often have the students concoct their own story problems. Lately, I’ve been using a tablet-based drawing tool along with some stickers from Byte. (I would love to use Byte—but it doesn’t live up to COPPA.)

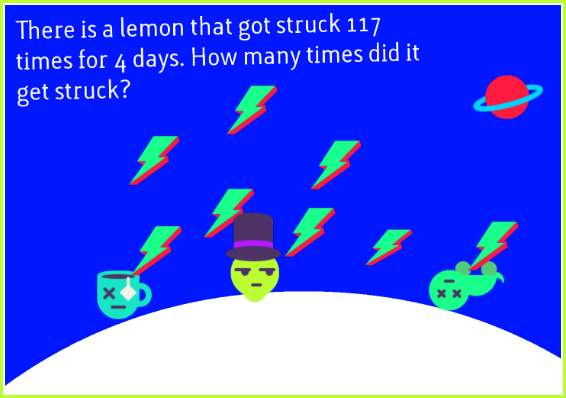

One kid came up with the pictured story problem. Pardon the grammar—we didn’t proofread these.

To clear this up: the lemon is struck by lightning 117 times each day! This lemon also appears to be alive, unlike the unfortunate turtle and teacup that found themselves stuck on the same hillside.

He is also probably actually a lime. How would that be—to have your key identity discarded during this defining moment? Maybe this is that elusive lemon-lime that the soft drinks always talk about.

Clearly we are dealing with a tough fellow here—an affluent, though morose, lemon-maybe-lime. We all hurriedly dashed out the answer so that we could know exactly how many strikings this poor citrus had endured! It was a tough four days.

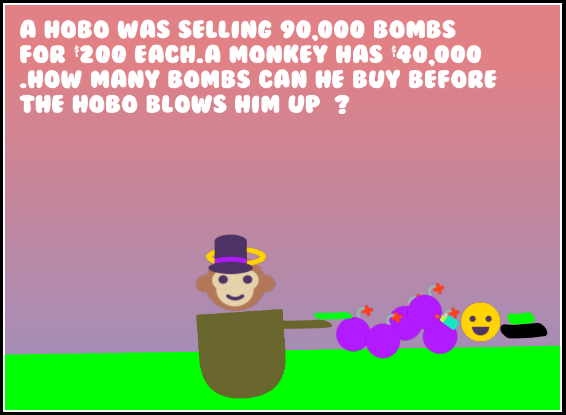

Now for this one.

I asked the student, “Will the hobo still blow the monkey up after he spends his $40,000?”

He said, “He’s going to blow him up no matter what.”

Wealthy monkeys, don’t do business with hoboes! Especially hoboes trafficking 18 mil in explosives! That seems suspicious to me.

The last story problem I want to mention never actually materialized, but this next one is a math-in-feelings problem.

It went like this:

(Student who has been at the counselor’s office arrives late for the activity.)

Me: “Ok, (Student). We’re coming up with story problems.”

Student: “Oh, I know what mine is!”

Me: “Let’s hear it.”

Student: “Ok. There are two guys. And they’re neighbors.”

Me: “Sounds good.”

Student: “And they hate each other in a hundred different ways.”

Me: “Oh, wow.”

Student: “But they love each other in a hundred different ways.”

Me: “So they cancel each other out.”

Student: “No, so you take all of their feelings—how many feelings all together do they have for each other?”

One of the kids next to us goes, “Four hundred feelings!” jubilantly.

This post accepts webmentions. Do you have the URL to your post?

You may also leave an anonymous comment. All comments are moderated.

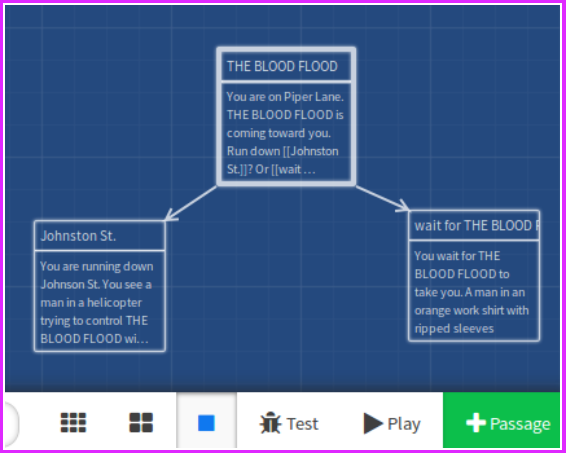

A detour: three weeks teaching Twine at school. Implications feel profound.

At the beginning of the year, the principal came to me and said, “I’m going to have you help with the after-school computer club. It’s a club for fourth- and fifth-graders.”

I was like, well, yeah, I’m the computer teacher, that makes sense.

She tells me the first grade teacher is in charge and I’ll just help her.

Perfect. This particular teacher is a close friend and this probably means we can do what we want.

“And code.org is going to give you all the stuff.”

Ok, no sweat. We’ll take a look.

A month ago, I walk into the first grade teacher’s room and she’s got this little pile of stuff on her desk.

I go, “What’s all this?”

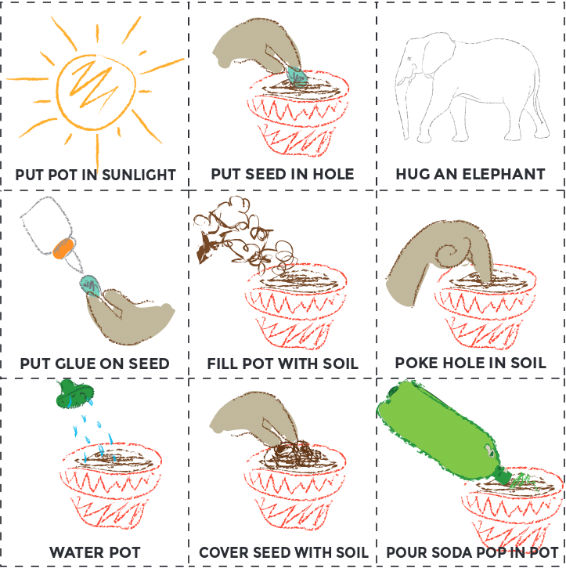

It’s the stuff from code.org. A cup. A packet of seeds. A gumball. Dirt.

She’s like, “I don’t get this.”

I clear a space and start to look over the paper she’s got—it’s this lesson plan that goes with the cup. And the dirt. (Wait—is that real dirt?)

Now, I’m just a computer teacher at a public elementary school—meaning I am absolutely the bottom of the chart on Career Day—like you do NOT bring up my job as some kid’s future—I am next to the guy selling Japanese dexterity games out of a kiosk at the mall—same guy who dresses in gold spandex and gets to be the Snitch in college Quidditch games—you don’t see him for two hours until you notice him above the quad, scaling the political science building—so, yes, a paltry elementary school computer teacher, but I have to tell you: I would never teach computer programming with a cup of dirt and a gumball. Nut uh. Not the way they’ve got this.[1]

So we bag that.

“Ok, good,” she says. “So I’m not crazy.”

She is. All humans are. But now’s not the time.

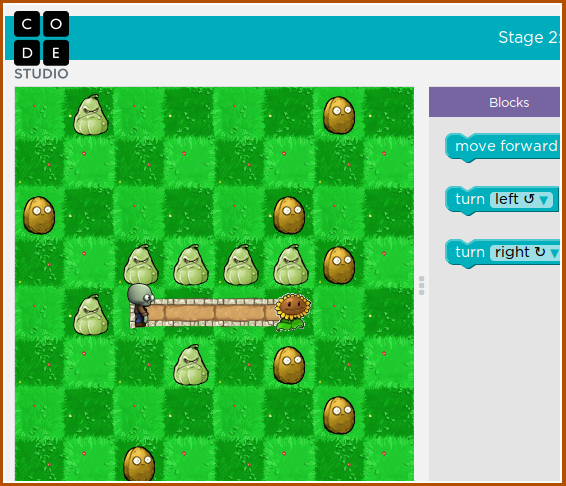

She seems relieved at first. Until she goes on. “So the next thing is: zombies.”

Couple clicks and her Macbook is showing the zombie lesson. In this lesson, all the kids get a zombie.[2] You basically control a zombie with code. You make it walk. Lurch forward, lurch left, lurch forward, lurch left, lurch left, lurch, lurch, lurch, then lurch right. That kind of thing.

“It’s not bad,” I say.

“I just don’t get why,” she says. “What is this for? Like: is this really teaching code?”

I’m thinking that, well, it kind of does—I guess?

“Code.org is like a million-billion dollar thing, isn’t it?”

“Well, Mark Zuckerberg,” she says. “And I think President Obama is in the video. Or he’s on the site or something.”

We look. Yeah, that IS Obama.

“So we’ll work for an hour and the kids will have made a zombie walk around a bit.”

So we bag that.

Fortunately—meaning this is where our fortune left the realm of mere dirt and a little bit of zombie walking—I had recently played a game called HIGH END CUSTOMIZABLE SAUNA EXPERIENCE. And somehow my thoughts turned toward this game, of which I recalled two things. For one, I remembered something about hacking into a cupcake in the game, which was certainly a fond memory. And then, the other thing, of course, what also came to mind, is that the game was a Twine game. A hypertext game. Made by Twine—some kind of neat way of building these games.

I pulled it up on her Macbook. Fifteen minutes later, we were like: “This. We are doing this.”

So we covered Twine for the first three weeks of the club. The first day we just showed them how to link.[3] This was actually plenty. I think this could have gone on for three weeks alone. One of the kids came up with this game THE BLOOD FLOOD. And, in his game, everywhere you went, THE BLOOD FLOOD showed up. Like this tsunami of gore.

Another girl came up with this game where you just lose. Over and over, you just lose. First you die. Then you lose a hundred points. Then your mom traps you and you lose. And then you die and you’re broke.

Great game. Pretty lifelike.

I expected the crazy stories. What really surprised me was: a kid showed me his project and it was a map of his family, done using Twine links. So he had links for his sister and mother and father and grandparents. And you could navigate his whole family and learn about them.

The creative story side didn’t appeal to him. He wanted to use the information housing and organization aspect of programming. It was a database.

So the kids universally loved the first week. (Kids love a lot of things, though.)

Second week we ran into problems getting everyone’s pages loaded. Not everyone was using the same laptop that they used the first week. So that can be a bit of a setback when using Twine—you’ll need to archive your stories and put them on a USB stick or something. Technically, the district’s user profile sync stuff should have brought down all the Chrome settings. However, I guess it doesn’t do anything with Chrome’s LocalStorage. So some kids had to start over. It was okay—they’re a resilient bunch. All humans are. But this problem, coupled with the time required to subsequently be resilient, meant we couldn’t cover as much.

We talked about the set: command and the if: command. The point was to help them see how to pick up things and how to give the player coins, swords and other trinkets one might take a-questing.

One kid wrote this dungeon where you could pick up a sword—and the sword is at 100%—so it’s like (set: $sword to 100).

And then, as you fight through the dungeon, the sword wears down.

So: (set: $sword to $sword - 5).

And then when it’s at zero, it’s useless.

(if: $sword > 0)[Take another [[swing]]?]

I was blown away by how much they could do with a simple variable and a conditional statement. I mean how. How are we spending time drawing shapes, lurching left, lurching right, when you can do all this great stuff with a variable and an if? I realize Papert did it this way—with shapes, with lurching—not with zombies but with turtles. Who am I to question Papert? Look him up on the career chart.

To me, this is incredible. On our first day, we were making actual games—text games, yes, but fun ones. I should have known better. I mean this is the generation that plays Minecraft for fun.

They were actually building the game logic. Like in a meaningful way—by turning these abstract constructs into concrete, actual iron swords that wear down.

The beauty of Twine is that your variables persist—they last the whole game. Doing this with straight JavaScript and HTML would be such a hassle to teach. There’s no need to understand scope or storage or anything like that. You’re just putting stuff in little cups. Not irrelevant dirt or gumballs. But REAL imaginary coins.

Initially I had planned to write some macros to help with inventory in Twine. I’m so glad I didn’t. By forcing the kids to use the basic constructs directly, they were able to grasp the rudiments and then apply those throughout their games.

Too often I see sites (like codecombat.com comes to mind) which give a kid an API to use. Like useSword(), turnRight(), openDoor(). I can’t understand this. It is teaching the API—not the simple constructs. Anyway, should we really be starting right into objects, methods, arguments and all that?

Our third lesson covered adding images, music, colors and text styling. I’m not as happy with Twine’s absence of syntax here—you’re basically just doing HTML for most things. But I also felt it would be good for them to dip their toes in HTML. For some kids, they didn’t care to take the time to use this tougher syntax just to put a picture in there.

They also struggled with stuff like (text-style: “rumble”). They loved the effect—esp. the two girls doing a graveyard adventure—but they didn’t like having to get everything perfect—the double-quotes, the colon, the spacing. This kind of syntax is a hurdle for them. Typing skills are still needed. This is a generation of iPhone users.

In all, my experiment using Twine went great—super great—they could do this every week and be content. There are a lot of movements out there to try to teach computer hacking, but they all really miss the mark in a way that Twine doesn’t. They don’t get railroaded into solving mazes. The kids come away with a real game.

In case you don’t believe me: Real-life Algorithms. ↩︎

Twine kind of follows the wiki-style of linking. You simply surround a phrase by double square brackets. Like so: [[Johnston St.]] Now it’ll create a new story page for Johnson St. ↩︎

This post accepts webmentions. Do you have the URL to your post?

You may also leave an anonymous comment. All comments are moderated.

How to teach — with an eye to Plato and Vygotsky

It was Christmas—and I binged on Piaget videos. And later that week, the grainy Seymour Papert documentaries where he has kids acting like robots in a field. Left! Left! LEFT! And I made several meals of Susan Engel’s essay on Curiosity. And then had it all dashed apart by Vygotsky.

Okay. Good. However—how should I teach? All this theory swimming around so impressively. What to actually say and do?

I was recommended The Educated Mind by Bret Victor at the 20 minute mark in a talk of his[1]. Turns out this is truly a lovely book. It attempts to sum up all the theory. Everything from Plato to Piaget, Vygotsky to Carl Sagan. (Even devoting a hearty portion to irony—a virtue which never seems to get its due.) After half the book mulling over the theories, we move into practical discussion of how to materialize all of this lofty thinking into teaching our real classes. Much like the real classes I teach in one corner of an old brick elementary.

Now, it’s funny. At the same time that I find myself troubled with how to teach, I realize there is almost no other way to do this. As the King of Hearts said, “Begin at the beginning and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

We recapitulate. We take a young one through the alphabet and all the numbers and symbols, the great novels and how to sketch with perspective and how to disassemble a frog—all that we once went through. We relive a history with them.

It is through this interiorization of historically determined and culturally organized ways of operating on information that the social nature of people comes to be their psychological nature as well.[2]

This interiorization happens through understanding. Kieran Egan covers the many ways of understanding—he lists his five most crucial types—like Mythically, in which we deal with binary concepts and construct imaginary beings that dwell at the extremes. Romantically, in great stories that pretend to have some grand purpose. As well as Philosophic, Somatic and Ironic.

These are not mere gimmicks. We often rely, in small children, on their mythical understanding. We don’t need to explain Hansel and Gretel.

The narrator does not explicitly discuss and explain the concepts of opposition—in this case, security and fear. We presuppose that in some profound way children already know these concepts; the narrator is using their familiarity to make events in some distant forest at some distant time meaningful.[3]

These early chapters on mythical and romantic understanding are wonderful. The mythical section studies the import of fairy tales and Peter Rabbit to toddlers; the romantic part studies both Herodotus and The Guinness Book of World Records, the appeal of high drama and human limits to adolescents. I found so many of his questions to be top notch.

[B]y far the most common learning principle urged on teachers is that children’s learning moves “from the known to the unknown,” and that, to engage their interest and make new knowledge meaningful, one must begin with something relevant to their everyday experience and connect the new knowledge to that. If this indeed is how children learn most effectively, one must wonder what does the fattest person who ever lived have to do with their everyday experience, or the most expensive postage stamp, or the longest beard?[4]

So the theory isn’t too detached from practice. Find the extremes in the subject you’re teaching, the soul of it. Play to the bizarre and the novel. It’s not quite as simple as that, of course—leave room for a touch of irony.

By preserving the earlier kinds of understanding as much as possible, we may develop a kind of irony that enables its users to recognize validity in all perspectives, to believe all metanarratives, to accept all epistemological schemes, to give assent to every belief. […] we do have other pursuits than understanding, and for some of the more exotic amoong them magic will trump science.[5]

Wow, this kind of thing has got to be a heresy in today’s society! The predominant notion today is that our goal is progress, our goal is a perfect truth and knowledge. To be brought back to Socrates and Nietzche—who suggested that the pursuit of truth is only driven by “wanting to be superior”[6]—gives the feeling of an old great truth: that we are really just working with scraps of the universe here. Not the keys to ultimate truth that we pretend.

As a technology teacher, this helps remind me that maybe technology is more of a magical substance than it is a great medicine for society. A realization that cannot come quick enough now that our ideals about social media have been dispelled by the absence of the interpersonal advances we were promised. No, it was all just a trick of getting messages from here to there, not a new form of living.

The final chapters take apart how to structure actual lessons. He falters a bit here—I feel there aren’t quite enough good examples given. But he does give a few very good ones. Such as when he discusses teaching about the air around us in a mythical way.

All in all, though, very near five stars here. I read books not to agree with the authors, but to think. To mull over someone else’s thoughts, in order to find where mine stand. But this book very much influenced me. I know I will be staying close to it from now on.

This post accepts webmentions. Do you have the URL to your post?

You may also leave an anonymous comment. All comments are moderated.

glitchyowl, the future of 'people'.

jack & tals, hipster bait oracles.

maya.land, MAYA DOT LAND.

hypertext 2020 pals: h0p3 level 99 madman + ᛝ ᛝ ᛝ — lucid highly classified scribbles + consummate waifuist chameleon.

yesterweblings: sadness, snufkin, sprite, tonicfunk, siiiimon, shiloh.

surfpals: dang, robin sloan, marijn, nadia eghbal, elliott dot computer, laurel schwulst, subpixel.space (toby), things by j, gyford, also joe jenett (of linkport), brad enslen (of indieseek).

fond friends: jacky.wtf, fogknife, eli, tiv.today, j.greg, box vox, whimsy.space, caesar naples.

constantly: nathalie lawhead, 'web curios' AND waxy

indieweb: .xyz, c.rwr, boffosocko.

nostalgia: geocities.institute, bad cmd, ~jonbell.

true hackers: ccc.de, fffff.at, voja antonić, cnlohr, esoteric.codes.

chips: zeptobars, scargill, 41j.

neil c. "some..."

the world or cate le bon you pick.

all my other links are now at href.cool.

Reply: Young Coder

Yeah, Twine is the real deal—to me, third to sixth is the ideal group for this tool. They’ve got down how to write, but may not yet see how useful writing can be. There’s a lot of negativity (in my experience) among this age group (in 2019) concerning writing—especially with video becoming so prevalent.

So I see Twine as a writing platform with coding playing a support role. This is awesome—because often kids will look at it as a ‘coding’ platform and not realize how much writing they are doing. I think this dual nature makes it incredibly powerful.

Sure, feel free to cite or syndicate anything here. I’m just glad you’re having the conversation. I’m definitely keeping an eye on your blog. Let’s be friends!